Conducted in depth and projected at length

AnaBritannica

1986

Vulnerability Trees

Mustafa Erdem Özler

2013

A Turkish Island on the Danube

Ahmed Emin Yalman

1915

New Adakale

2014

Dictionary

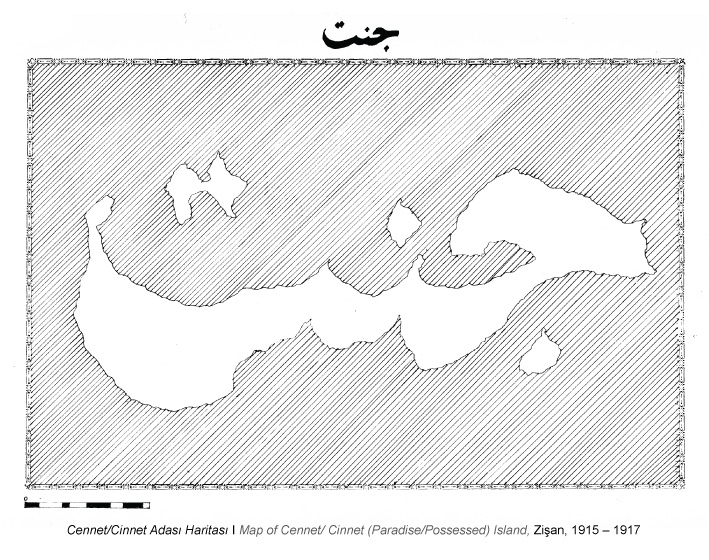

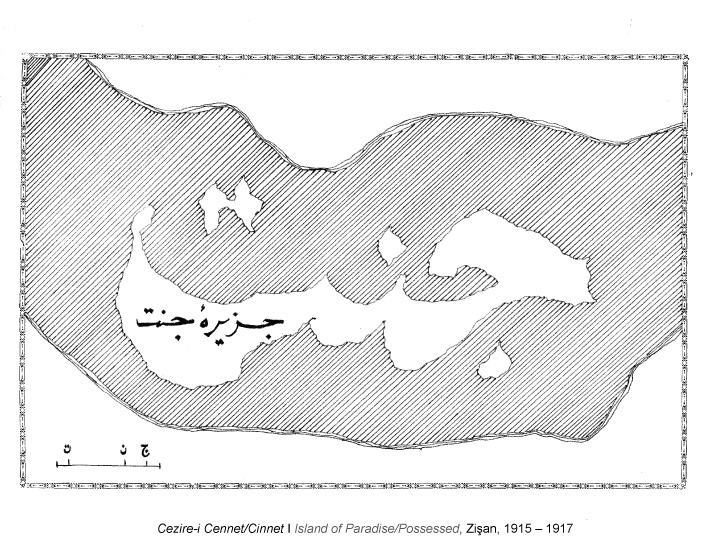

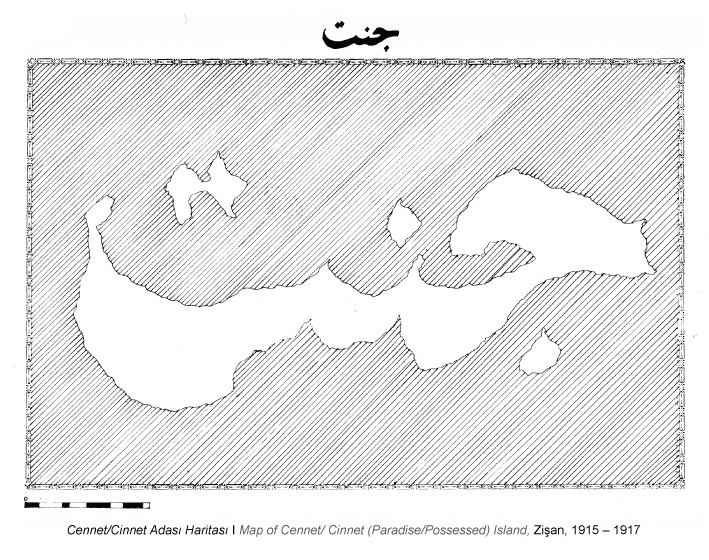

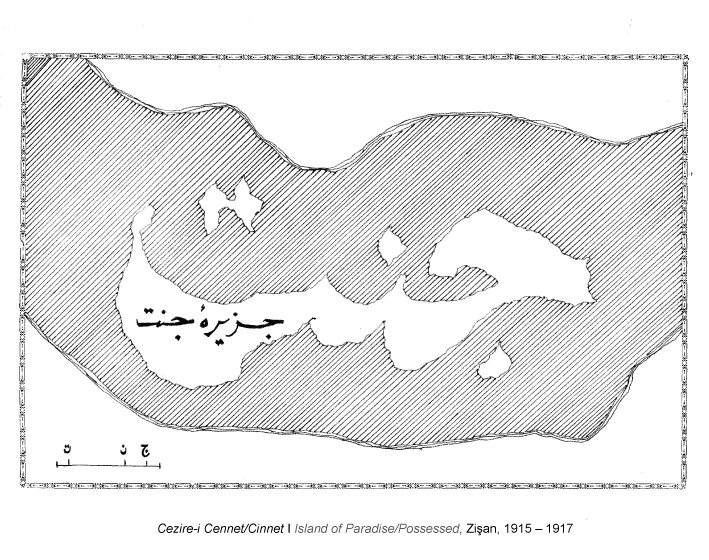

Island of Paradise/Possessed

Zişan

1915-1917

Bibliography and

Works

Biographies

In Conversation with Zişan

İz Öztat and Zişan

2014

In Conversation with Zişan

İz Öztat and Zişan

2014

Bibliography and

Works

Island of Paradise /Possessed

Zişan

1915-1917

AnaBritannica

1986

A Turkish Island on the Danube

Ahmed Emin Yalman

1915

New Adakale

2014

Dictionary

Vulnerability Trees

Mustafa Erdem Özler

2013

Biographies

İZ: Now, we meander through the course of a discourse that accumulates on the shores. Drifting between various flows of time—the time it takes for the river to claim its bed and an for island to emerge, the time required for an island to become a territory, the time one devotes to being possessed, the time invested in taming and interrupting the flow of water until an island is flooded, the movement of articulating a drifting island in the present, the vision of a future which reconstructs the island as a tourist attraction, the time necessary for shaping the course of discourse dedicated to imagining otherwise—we search for something missing.

We establish our contact around a coincidence between the imaginary potential of a river island and the destiny of Adakale, a submerged island in the Danube River within the borders of present-day Romania.

In Conversation with Zişan

What was your first encounter with Adakale?

ZİŞAN: I remember reading about the island in Ahmet İhsan’s travelogue, A Week in the Danube, in which the island was mentioned as “The last plaintive sign of the Ottomans on the Danube.” Forgotten in the Congress of Berlin, Adakale was an Ottoman exclave in the Balkans until 1923 and became the site of projected imperial longings.

ZİŞAN: Narratives we inherit reflect the human tendency to project paradises on islands as they hold the promise of absolute autonomy gained through closure and totality in remote places. With Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet, I search for the notion of a river island that is not too far away from the mainland but can still maintain its autonomy. In the story, the commune strives for an alternative society as they learn from the qualities of the place that they inhabit. They gather the strength to exist in an ambugious, consequently vulnerable reality, which would be a deviation towards cinnet [mania] for those abiding by the norms on the shores near by.

When I was a child, cinnet and all the other words referring to madness were banned by Abdülhamid II so that the people would not be reminded of his brother Murad V, who was dethroned due to his madness. It is not a surprise that a banned word returns as the setting of another possibility in the work.

İZ: As you were growing up, you were familiar with the utopia of Yeşil Yurt (Green Country) perpetuated by some members of the Servet-i Fünun literary circle. They were suffocating under the autocratic rule of Sultan Abdülhamid II and dreamed of escaping to New Zealand as a group. If not an escape, what is a river island for you?

İZ: How did Adakale become a source of inspiration for your utopian story titled Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet (Island of Paradise/Possessed)? Did you ever see the island?

ZİŞAN: The island was on our exile route… Right before Talat Pasha issued and implemented the Tehcir Law in 1915, a secret was revealed to me by Nezihe Hanım and Diran Bey, which required me to reorient myself to the world. I grew up in Nezihe Hanım’s house as an orphan and spent lots of time in the studio of Diran Bey, an Armenian photographer. They told me that I actually was their daughter, born out of a secret affair. Fearing for his life, Diran Bey decided to flee from Istanbul and try to make it to Berlin with the help of his anarchist friends from Sofia. They asked me if I want to stay in Istanbul or go with Diran Bey. I decided to join him and we left on a boat to Constanza the next morning… During the journey up the Danube River, I saw Adakale as we passed by. Moving through a landscape devastated by national and imperial struggles, the river island became a speculative instrument for wishing and imagining an alternative. I started writing the story then and occasionally worked on it for the next two years.

İZ: The island in your story is in the shape of which can be read both as cennet (paradise) and cinnet (possessed, mania) in Ottoman since the vowels are not written. Why did you choose this word, which implies both utopia and dystopia, as the setting of your imaginary island?

ZİŞAN: Being infatuated with the propaganda material produced by the English to repopulate the colonized island of New Zealand, they desired to escape to an existing island. They wanted to leave because they could not dare to resist. Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet is an imaginary river island inhabited by dissidents, who can collectively articulate an alternative by allowing the island itself to emerge as a subject that suggests an empowering way of life for its population.

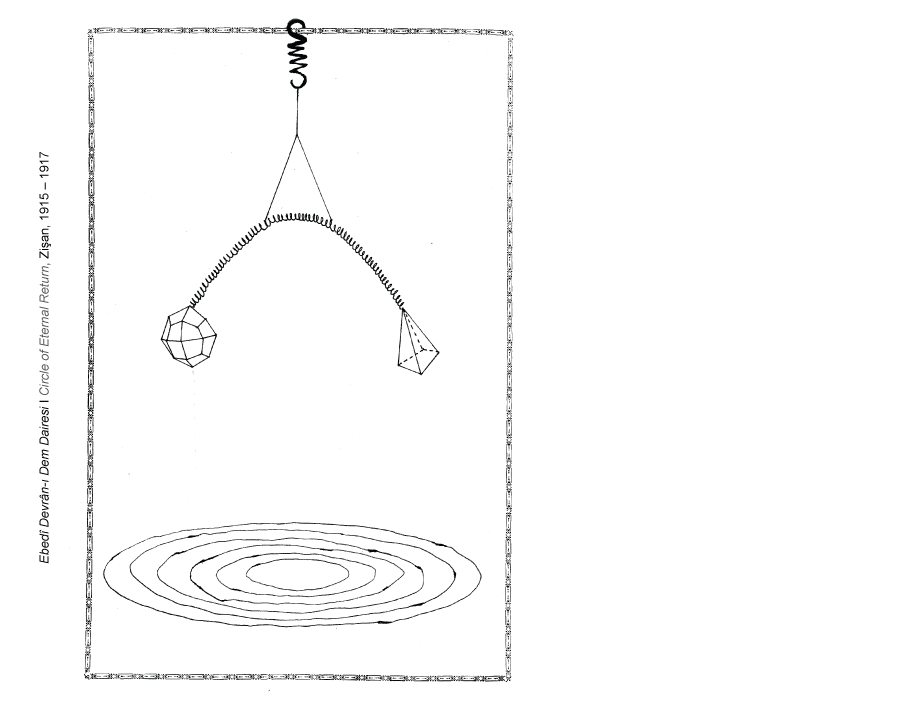

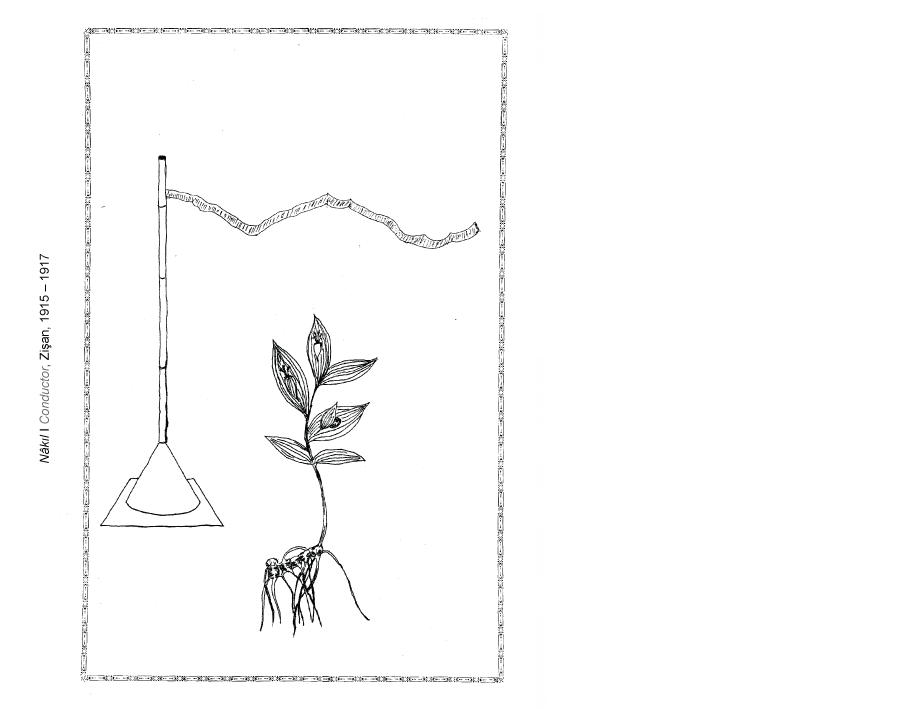

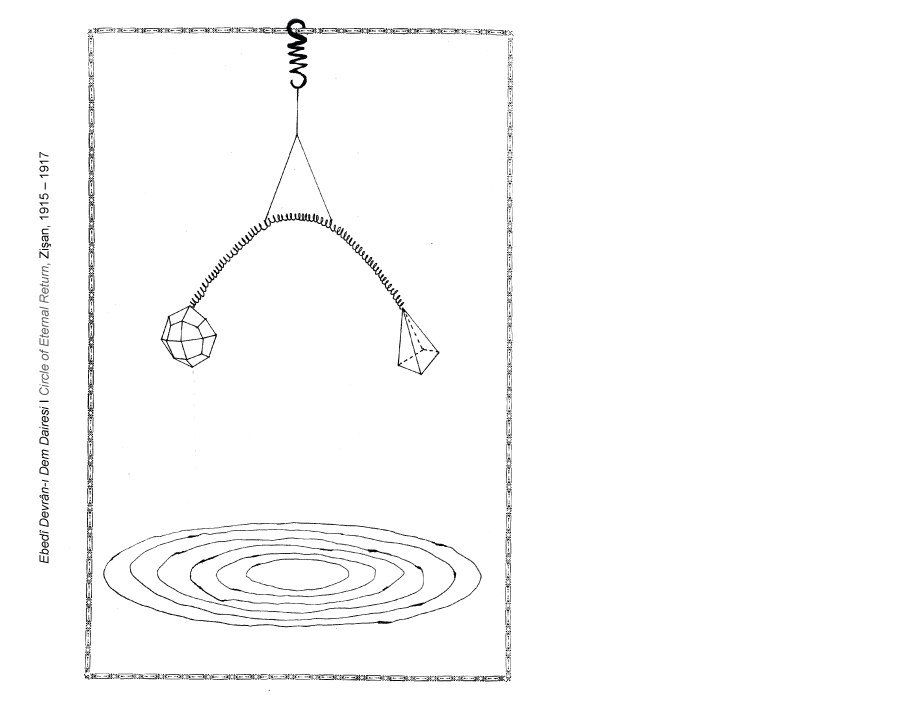

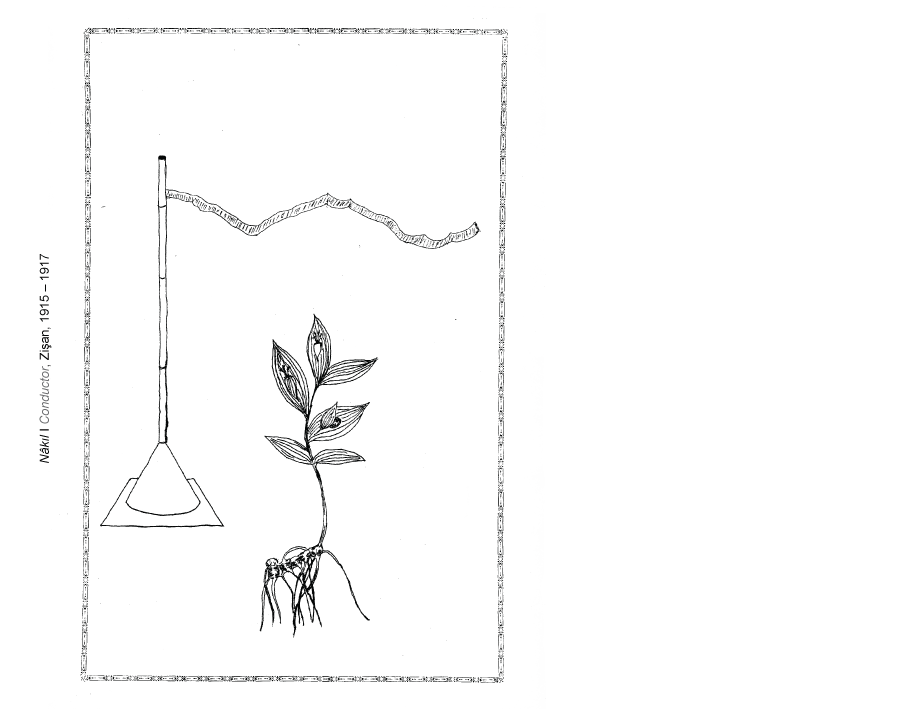

İZ: In the story, the obscure devices, which trigger rituals for relating to time differently and gaining esoteric knowledge, play a significant role. Why is esoteric knowledge so central to your imagined community?

ZİŞAN: In the story, esoteric knowledge is gained by listening to the landscape and treating it as a source with agency, not as a resource to be manipulated. Although this attitude manifests as having access to esoteric knowledge in the story, the underlying assumption is treating one’s environment as a living being with its ecosystem and cosmology.

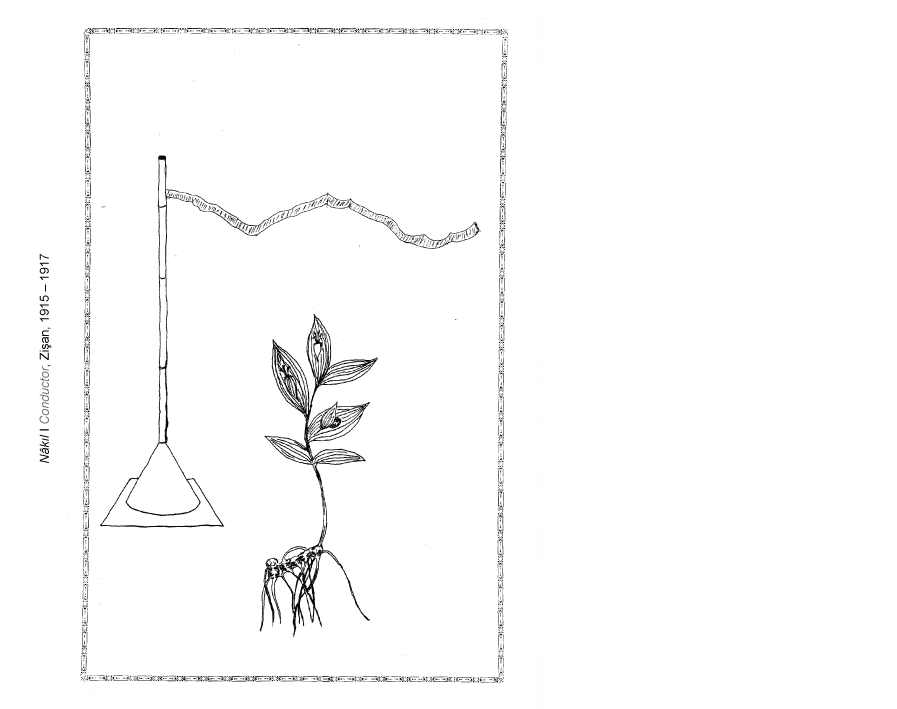

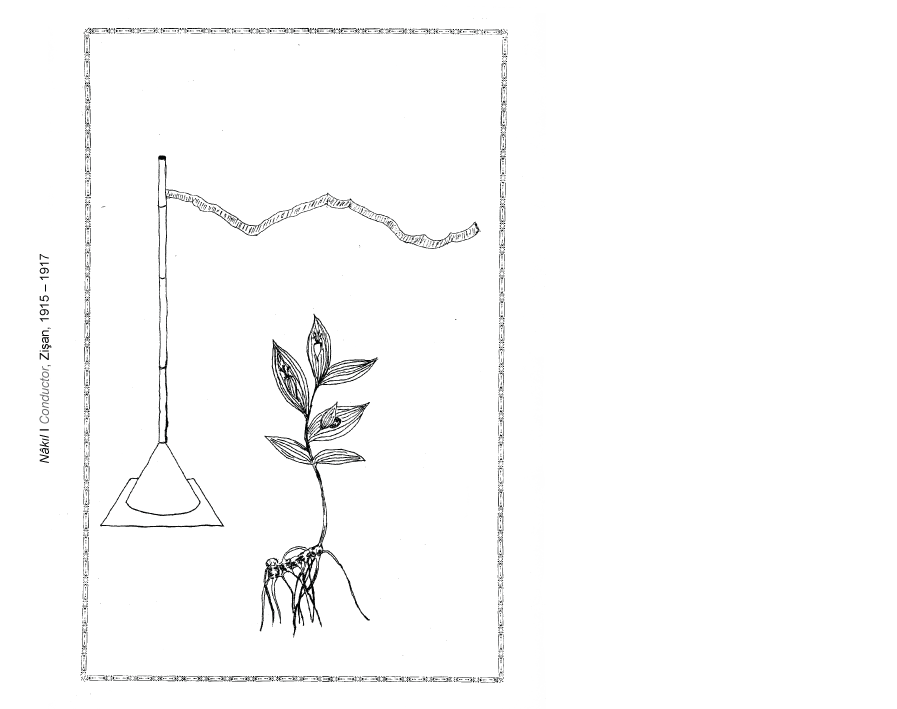

The relationship to time and history is not dictated from above but is articulated and transformed in individual experiences. Through the rituals triggered by the devices; conductor and circle of eternal return, each individual influences collective memory with what they remember and forget. Crafting organic materials is central to the realization of the devices. They are inspired partially by the irrational machines of Picabia…

Now, shall we move into your flow?... How do you coincide with Adakale?

İZ: I came in contact with the island in 2012 upon your request. What strikes me in the existing narratives surrounding the island and its people is that they have no agency in shaping their destiny. The island is repopulated, forgotten, longed for, exoticised and submerged. Its population complies.

Neither the island, nor its people figure into these narratives as subjects. They submit to imperial and national agendas, benefit from being a tourist attraction and are displaced with the logic of progress as the Iron Gates Dam is built in 1968 by Tito and Ceaușescu. What is left of the island now is nostalgia for a lost paradise and attempts to reconstruct it as a theme park on the near by Şimian Island, where remains of the castle are kept.

ZİŞAN: How do you respond to this narrative and the absence of the island?

İZ: I see the destiny of the absent island as a coincidence that intersects with the untimely encounter between us. I follow your impulse to treat the island as a speculative instrument for imagining otherwise. I must also admit that the idea of an imaginary river island allowed for an escape in "times we can't pass through our insides". I found pleasure in drifting along the coasts of Cennet/Cinnet Island, reconstructing the devices and connecting with you through these processes.

ZİŞAN: But you are also concerned with the absence of the island and the contemporary life surrounding it. You went to Orşova, Romania and visited the site of the absent island. What did you see and how did you respond?

İZ: I arrived there wondering about the potential of the river and the island as concepts: If the river is a creature of engineering and the island is gone, what can be speculated?

I observed that the main connection people of Orşova have with the river is rowing on canoes as sports and leisure activities. Rowing had a practical function in everyday life once, when the island was there and the river was flowing… I went to the sports club and asked a group of people if they could move in a circle for me to capture on video. In the action of eleven people rowing together to constitute a circle, I projected my desire for a drifting river island articulated collectively.

Afterwards, I learnt that they were actually members of the Junior National Kayaking Team. What I imagined to be self-determination emerging from collective movement was actually made possible with the discipline of a national sports team. I don’t know how to reconcile the two…

ZİŞAN: You challenged me earlier for gravitating towards esoteric knowledge as the source of collective resistance but as you have also experienced, manifestations of the utopian wish are inherently vulnerable, fragile and even naïve. Yet, we can still discover alternative methodologies for commoning and other collective imaginaries in them…

İZ: Thanks for drifting me into your flow and dreaming with me!

ZİŞAN: I thank you for the time you devote to me…

FACTS

İz Öztat, 2014

Danube: Reduced and Simplified

Adapted for publication, flowing through the pages

İz Öztat, 2014

Channeling with Conductor

(...) To be fond of Adakale did not require to see the island in person. This place is the only monument left behind by the old, proud times. This is a live, precious national museum for us. From this point of view, the island should remain ours, the Ottoman flag should continue to wave on the Danube. For us, the island holds a greater value than just from an emotional perspective. From this perspective, we could be certain that our Austria-Hungarian allies will abide by our national feelings and will not do anything that will offend us. The situation should not be limited to a bond to Adakale from afar. The Danube island should become a national site of visitation. Every year, visitors from all around the country should visit Adakale during appropriate national holidays and do things here that will vouch for memories of the past. With this occasion, we can hold a ceremony of fraternity with our Hungarian brothers at a neighboring location. There is a second and important issue. In order for Adakale to retain its national value, the community should be pure, true Turks. The incomrepehensible record of preservation sufficed to sustain the island as Turkish up until recently. Across the shore, selling tobacco, coffee and sugar, working as coffee-servers on the Danube boats, selling knick knack to the visitors of the island, ensured a well-off life.

Away from the other parts of the motherland, as they are not subjected directly to power of national distress, it is possible that the inhabitants of the island will start considering the national perspective lightly. It is not impossible that some will be tempted by the obvious allures of the shores across to penetrate the island with tides that are outside of the national elements. The only thing to be done against this, in order to evoke national feelings on the island, is to realize an internal and strong border that will stand against the detrimental impact, without delay. The minister, judge, imam and teacher on the island who represent the national and social forces on the island, are competent men of their professions. Under conditions in which anyone who is having a difficult time could just cross to the shore across and the state does not possess the power to reinforce anything, these men exhibit a pleasing level of authority to get their job done. Help should be delivered and the inhabitants of Adakale should feel that millions of eyes are on them, and that their island is important, their actions scrutinized. The small community of individuals on Adakale should thus be supplemented with influence and authority from the motherland; if the generation that is raised with the help of the national impact, Adakale will remain ours forever.

The Turkish Island on the Danube Ahmed Emin Yalman

Adakale postcard from Zişan’s archive, date not specified.

times we couldn’t pass through our insides

until an abdülhamid begins and ends

Mustafa Erdem Özler, from the poem “İncinir Ağaçları” [Vulnerability Trees], Tarihi Ayı Öfkesi [Historic Bear Rage], Metis Publications, Istanbul, November 2013

Tanin Newspaper, November 23rd, 1915

Adakale is an island located on the Strait of Demirkapı, opened up by the Danube river between the Panet mountains, now submerged underwater because of the construction of a dam.

Turks settled on the island at the beginning of the 15th century. After building a castle here to prevent Austrian attacks, it was called Adakale (lit. Island castle). When the Ottoman garrisons withdrew from Serbian castles in 1867, the island was separated from the Ottoman land, but as the population was fully Turkish, it was effectively still connected to the Ottomans. With the 1878 Ayastefanos (Yeşilköy) agreement, it was decided that the island was to be evacuated, the Ottoman State used the absence of a note affirming this decision at the Berlin Congress to designate a township warden and a judge, continuing their rule here. The island was shown as a part of the Ottoman land in governmental annuals; after World War I, with the Trianon agreement dated 1920, it was transferred to Romania through Austria-Hungary, but the Ottoman State never accepted this decision. In 1923, with the Lausanne agreement, Adakale was officially given to Romania.

In Romania, the only settlement that was made up of Turks was Adakale. In 1967, it had 150 households and a population of 750. The community made their living through being boatmen and making coffee on touristic boats on the Danube. The architectural structures were single-floor, constructed of stone, and had brick roofs; there was a mosque on the island with a single minaret. The Adakale community wrote and spoke Turkish and preserved Turkish traditions for five-hundred years. Ignacz Kunos, a Hungarian Turkologist, gathered around 100 Adakale songs.

Adakale was submerged by the waters of a dam that was built in 1970; the population moved elsewhere.

AnaBritannica: General Knowledge Encyclopedia, 1st Edition. İstanbul: Ana Yayıncılık, 1986.

İz Öztat, 2014

Constituting an Island

Single channel HD video, 1’46''

İctimâî: Toplumsal, sosyal

İdâre-i umûr: İşlerin görülmesi

İrtibât: Bağlantı, bir şeyle ilgili olma hali

İstikbâl: Gelecek

İştirâk etmek: Katılmak

İtibâr etmek: Saygı göstermek, önem vermek

Îzâhât: Açıklamalar

Kâfî: Yeterli

Kaide: Kural

Kanâat getirmek: Bir konuda bir görüşe varmak

Kıymet-i milliyye: Milli değer

Kuvâ-yi milliyye ve ictimâiyye: Milli ve sosyal güçler

Kuvve-i te’yîdiyye: Pekiştirme kuvveti

Lâhza: An

Lûgatçe: Küçük sözlük

Mâder vatan: Anavatan

Mâî: Mavi

Mâlik: Sahip

Malûmât: Bilgi

Ma’tûf: Yönelik

Mecrâ: Suyun aktığı yatak, su yolu

Memâlîk: Memleketler, ülkeler

Menba: Kaynak

Merbûtiyyet: Bağlılık

Mesuliyyet: Sorumluluk

Meyletmeyen: Eğilim göstermeyen, yönelmeyen

Mizâc: Huy, kişilik

Muâvenet: Yardım

Muğlak: Belirsiz

A Turkish businessman, who doesn’t want to disclose his name, rented Şimian Island for 49 years to revive Adakale’s history. Şimian Island, where remains of Adakale’s castle, graveyard and other historical artifacts have been moved prior to the construction of the dam, will be restored as “New Adakale.” A miniature park, which includes miniature buildings representing Romania’s cultural heritage and emphasizing Turkey’s historical and cultural values, will be realized. On the island that covers a 55.5 hectares area, hotels, landscaping, spaces to exhibit the historical heritage of Adakale, sports facilities, a casino, restaurants, a harbor, parks, little forests, education and treatment centers will be executed. With this mega project, which will be completed in five years, New Adakale will become a tourist attraction on the Danube.

New Adakale

Compiled from various websites between 2012-2014.

* The original text was written in Ottoman. It has been transliterated, adapted to Turkish, then translated to English. Due to the Language Reform (1932), which aimed at replacing Arabic and Persian words used in the Ottoman language with invented words of supposedly Turkish origin, many of the words in the original text are not currently in use.

Island Of Paradise

/Possessed

I was moving along the river. The burden that I assumed would subside as I approached the source of the water and the violence that I hoped I could escape, were making themselves felt; I was not able to avoid the haunting voices of the revenants. When I stopped to rest, I noticed the island in the middle of the river. I gestured and made a deal with a boatman to take me to the island.

At a garden I reached through the tunnels of a castle that surrounded the island, I happened upon a strange ritual. For a long time, I watched the figure breathing into a transparent thing, extending from a pipe placed on a copper base. Upon opening hir eyes and noticing that I was watching, s/he approached me. I introduced myself, saying that I came by coincidence and I needed a place to stay for the night.

Zişan, 1915 - 1917

İZ: Now, we meander through the course of a discourse that accumulates on the shores. Drifting between various flows of time—the time it takes for the river to claim its bed and an for island to emerge, the time required for an island to become a territory, the time one devotes to being possessed, the time invested in taming and interrupting the flow of water until an island is flooded, the movement of articulating a drifting island in the present, the vision of a future which reconstructs the island as a tourist attraction, the time necessary for shaping the course of discourse dedicated to imagining otherwise—we search for something missing.

We establish our contact around a coincidence between the imaginary potential of a river island and the destiny of Adakale, a submerged island in the Danube River within the borders of present-day Romania.

What was your first encounter with Adakale?

ZİŞAN: I remember reading about the island in Ahmet İhsan’s travelogue, A Week in the Danube, in which the island was mentioned as “The last plaintive sign of the Ottomans on the Danube.” Forgotten in the Congress of Berlin, Adakale was an Ottoman exclave in the Balkans until 1923 and became the site of projected imperial longings.

In Conversation with Zişan

ZİŞAN: Narratives we inherit reflect the human tendency to project paradises on islands as they hold the promise of absolute autonomy gained through closure and totality in remote places. With Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet, I search for the notion of a river island that is not too far away from the mainland but can still maintain its autonomy. In the story, the commune strives for an alternative society as they learn from the qualities of the place that they inhabit. They gather the strength to exist in an ambugious, consequently vulnerable reality, which would be a deviation towards cinnet [mania] for those abiding by the norms on the shores near by.

When I was a child, cinnet and all the other words referring to madness were banned by Abdülhamid II so that the people would not be reminded of his brother Murad V, who was dethroned due to his madness. It is not a surprise that a banned word returns as the setting of another possibility in the work.

İZ: As you were growing up, you were familiar with the utopia of Yeşil Yurt (Green Country) perpetuated by some members of the Servet-i Fünun literary circle. They were suffocating under the autocratic rule of Sultan Abdülhamid II and dreamed of escaping to New Zealand as a group. If not an escape, what is a river island for you?

İZ: How did Adakale become a source of inspiration for your utopian story titled Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet (Island of Paradise/Possessed)? Did you ever see the island?

ZİŞAN: The island was on our exile route… Right before Talat Pasha issued and implemented the Tehcir Law in 1915, a secret was revealed to me by Nezihe Hanım and Diran Bey, which required me to reorient myself to the world. I grew up in Nezihe Hanım’s house as an orphan and spent lots of time in the studio of Diran Bey, an Armenian photographer. They told me that I actually was their daughter, born out of a secret affair. Fearing for his life, Diran Bey decided to flee from Istanbul and try to make it to Berlin with the help of his anarchist friends from Sofia. They asked me if I want to stay in Istanbul or go with Diran Bey. I decided to join him and we left on a boat to Constanza the next morning… During the journey up the Danube River, I saw Adakale as we passed by. Moving through a landscape devastated by national and imperial struggles, the river island became a speculative instrument for wishing and imagining an alternative. I started writing the story then and occasionally worked on it for the next two years.

İZ: The island in your story is in the shape of which can be read both as cennet (paradise) and cinnet (possessed, mania) in Ottoman since the vowels are not written. Why did you choose this word, which implies both utopia and dystopia, as the setting of your imaginary island?

İz Öztat, 2014

Constituting an Island

Single channel HD video, 1’46''

ZİŞAN: Being infatuated with the propaganda material produced by the English to repopulate the colonized island of New Zealand, they desired to escape to an existing island. They wanted to leave because they could not dare to resist. Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet is an imaginary river island inhabited by dissidents, who can collectively articulate an alternative by allowing the island itself to emerge as a subject that suggests an empowering way of life for its population.

İZ: In the story, the obscure devices, which trigger rituals for relating to time differently and gaining esoteric knowledge, play a significant role. Why is esoteric knowledge so central to your imagined community?

ZİŞAN: In the story, esoteric knowledge is gained by listening to the landscape and treating it as a source with agency, not as a resource to be manipulated. Although this attitude manifests as having access to esoteric knowledge in the story, the underlying assumption is treating one’s environment as a living being with its ecosystem and cosmology.

The relationship to time and history is not dictated from above but is articulated and transformed in individual experiences. Through the rituals triggered by the devices; conductor and circle of eternal return, each individual influences collective memory with what they remember and forget. Crafting organic materials is central to the realization of the devices. They are inspired partially by the irrational machines of Picabia…

Now, shall we move into your flow?... How do you coincide with Adakale?

İZ: I came in contact with the island in 2012 upon your request. What strikes me in the existing narratives surrounding the island and its people is that they have no agency in shaping their destiny. The island is repopulated, forgotten, longed for, exoticised and submerged. Its population complies.

Neither the island, nor its people figure into these narratives as subjects. They submit to imperial and national agendas, benefit from being a tourist attraction and are displaced with the logic of progress as the Iron Gates Dam is built in 1968 by Tito and Ceaușescu. What is left of the island now is nostalgia for a lost paradise and attempts to reconstruct it as a theme park on the near by Şimian Island, where remains of the castle are kept.

ZİŞAN: How do you respond to this narrative and the absence of the island?

İZ: I see the destiny of the absent island as a coincidence that intersects with the untimely encounter between us. I follow your impulse to treat the island as a speculative instrument for imagining otherwise. I must also admit that the idea of an imaginary river island allowed for an escape in "times we can't pass through our insides". I found pleasure in drifting along the coasts of Cennet/Cinnet Island, reconstructing the devices and connecting with you through these processes.

ZİŞAN: But you are also concerned with the absence of the island and the contemporary life surrounding it. You went to Orşova, Romania and visited the site of the absent island. What did you see and how did you respond?

İZ: I arrived there wondering about the potential of the river and the island as concepts: If the river is a creature of engineering and the island is gone, what can be speculated?

I observed that the main connection people of Orşova have with the river is rowing on canoes as sports and leisure activities. Rowing had a practical function in everyday life once, when the island was there and the river was flowing… I went to the sports club and asked a group of people if they could move in a circle for me to capture on video. In the action of eleven people rowing together to constitute a circle, I projected my desire for a drifting river island articulated collectively.

Afterwards, I learnt that they were actually members of the Junior National Kayaking Team. What I imagined to be self-determination emerging from collective movement was actually made possible with the discipline of a national sports team. I don’t know how to reconcile the two…

ZİŞAN: You challenged me earlier for gravitating towards esoteric knowledge as the source of collective resistance but as you have also experienced, manifestations of the utopian wish are inherently vulnerable, fragile and even naïve. Yet, we can still discover alternative methodologies for commoning and other collective imaginaries in them…

İZ: Thanks for drifting me into your flow and dreaming with me!

ZİŞAN: I thank you for the time you devote to me…

İctimâî: Toplumsal, sosyal

İdâre-i umûr: İşlerin görülmesi

İrtibât: Bağlantı, bir şeyle ilgili olma hali

İstikbâl: Gelecek

İştirâk etmek: Katılmak

İtibâr etmek: Saygı göstermek, önem vermek

Îzâhât: Açıklamalar

Kâfî: Yeterli

Kaide: Kural

Kanâat getirmek: Bir konuda bir görüşe varmak

Kıymet-i milliyye: Milli değer

Kuvâ-yi milliyye ve ictimâiyye: Milli ve sosyal güçler

Kuvve-i te’yîdiyye: Pekiştirme kuvveti

Lâhza: An

Lûgatçe: Küçük sözlük

Mâder vatan: Anavatan

Mâî: Mavi

Mâlik: Sahip

Malûmât: Bilgi

Ma’tûf: Yönelik

Mecrâ: Suyun aktığı yatak, su yolu

Memâlîk: Memleketler, ülkeler

Menba: Kaynak

Merbûtiyyet: Bağlılık

Mesuliyyet: Sorumluluk

Meyletmeyen: Eğilim göstermeyen, yönelmeyen

Mizâc: Huy, kişilik

Muâvenet: Yardım

Muğlak: Belirsiz

to feel responsibility towards the place where they established their lives and to respect it. Listening to the island and the water, they met their quotidian needs and formed a time and breathing cycle that veered away from accumulation. They realized that they could forget all they knew by washing themselves in the waters of the river, with the effect of the indigo-colored snails they collected from the shore, they could have a grasp of the island’s esoteric knowledge. Thus they built the ambiguous reality that enabled them to experience time in various forms. When they arrived at the island, they moved into the existing passages of the castle and as the population increased in number, they continued to live in a unibody space by constructing labyrnthine passages.

Zındık jumped to the sound of the bell and told me that dinner was prepared together and that we needed to start going towards the kitchen. The people who had gathered for the preparations

İz Öztat, 2014

Danube: Reduced and Simplified

Adapted for publication, flowing through the pages